[Version française sur le site de La Recherche]

Why do we want to go to Mars so badly? The first answer that comes to mind is: to look for alien life.

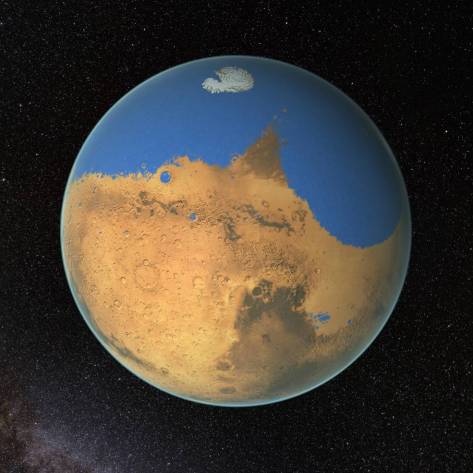

You might think that, being an astrobiologist, I am biased. And you are probably right: microbes matter to me more than rocks, and if you’re a geologist you’re probably yelling at your screen. But the search for life is usually at the top of mission objectives when it comes to Mars. Mars has not always been the dry, cold and desert planet it is today. Evidence suggests that, at some points in its history, it was surrounded by a denser atmosphere, had lakes, rivers and oceans, and was warmer. The large amounts of nutrient-rich volcanic rocks, together with atmospheric gas, likely provided all the elements needed to support microbial life forms as we know them.

That being said, the fact that a planet has everything it needs to sustain life does not mean that it sustains life. “Where there is water, there is life”, as you might have read quite a few times, is a naive affirmation based on what we observe in terrestrial environments. Put water in a bottle, as well as sugars and everything microorganisms need to thrive, close it, heat it enough to kill everything inside, and let it cool. As long as your bottle is closed, you will have an environment which is suitable for life but does not harbor it. That Mars used to be hospitable does not mean that it was inhabited.

It does not mean that it was not, either. In particular, it is quite possible that Mars was contaminated by terrestrial life. And I am not referring to the fact that we sometimes mess up when sterilizing rover drills; no, I am speaking about bacteria surfing rocks through space. Sounds surprising? Maybe. But large amounts of materials have been transferred from Earth to Mars, and vice-versa, after being expelled by asteroids or comets.

Throw a rock in gravel. Pebbles will be expelled from the impact, right? Throw it harder. Ejected pebbles will fly farther and faster. If you threw the rock so hard that the ejected pebbles flew away at 12 km/s (and were not destroyed by heat), they could leave Earth: 12 km/s happens to be just above what we call Earth’s escape velocity. Escape velocity is basically the speed you need to break free from gravity. In other words: if you go faster than a planet’s escape velocity, you can end up in space.

No offense, but I doubt that you could throw a rock hard enough to accelerate pebbles beyond Earth’s escape velocity. However, an asteroid impact can. Ejecta reaching escape velocity leave the planet and begin orbiting around the Sun, for hundreds of thousands or millions of years, until they either impact another celestial body or leave our planetary system. And asteroid impacts on Earth and Mars are quite common (on a geological time scale; no, no need to invest in an underground bunker).

Interestingly, evidence shows that life on Earth existed more than 3.5 billion years ago, and could have appeared there at a time when Mars was hospitable. This overlap could have favored microorganism survival after Earth-to-Mars contamination. Or… conversely. Yes. For various reasons, if Earth and Mars harbored the same density of life, Mars-to-Earth transfer would be more likely than Earth-to-Mars transfer. In particular, Mars’s escape velocity is lower than Earth’s: 5 km/s (and no, sorry, you still could not throw a rock into space from Mars; you might be able do it from one of its moons, though). Expelling a rock from Mars could be done more smoothly. At this point I can – maybe – tell you this without you calling a psychiatric hospital to check for missing patients: it is not impossible that life on Earth came from Mars.

That being said, being ejected from one planet by an asteroid impact, surfing an ejectum and crashing on another planet is quite a ride. Could bacteria – or more primitive forms of life – survive it?

The first issue is the pressure faced by rocks expelled by an asteroid impact. But shock recovery experiments (a fancy term for “putting bacteria in a bullet, firing the bullet, and looking whether bacteria are still alive”) show that some bacteria could survive a shock expelling a rock from Mars. Another issue is temperature, due to friction with the atmosphere when leaving a planet and entering a new one (if you quickly rub one of your hands against the other, you will quickly realize that friction creates heat). But rocks can be expelled from Mars without been excessively heated, and it has been assessed that billions of ejecta have travelled from Mars to Earth without being heated above 100°C, a fraction of which travelled for a time below the known lifespans of dormant bacteria. Then, there is the trip to space, which involves low temperatures, radiations, vacuum, and a few other things you would not enjoy being exposed to. But resistance of bacteria to space has been extensively studied in the past decades, in simulations on Earth but also on-board spacecraft, and it seems that some bacteria could survive the trip if sheltered inside a rock.

If Mars ever harbored microbial life, its natural transfer to Earth is a highly probable process. Consistently, structures found in Martian meteorites found on Earth are strongly suspected to be fossilized bacteria. The most suspicious ones are contained in the meteorite fragment ALH84001; 20 years after their discovery, the microfossil-looking shapes still lead to heated discussions within scientific communities. More heated than you would ever expect of conversations about a rock (except, maybe, if the rock was thrown at your face). If such structures were found in an ordinary rock, in an ordinary place, most biologists would conclude that they are fossilized microbes, and nobody would blame them for that. But as Carl Sagan said, “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence”, and we have no unquestionable evidence that those structures – or any structure found in Martian meteorites so far – come from bacteria that once lived on Mars. In spite of tantalizing clues and convictions of eminent scientists.

Another burning interrogation concerns the existence of current life on Mars. Life on the surface is unlikely given today’s harsh conditions there, but nothing excludes the possibility of underground microbes.

Has there been life on Mars? Does it come from Earth? Does life on Earth come from Mars? Is there life on present-day Mars? We will likely not come with any satisfying answer to those questions before humans walk on Mars’s red dust.

Cyprien, your argument for going to Mars is entirely convincing. And along with all of the important reasons, there’s another : we seem to be, as homo exploritatus, addicted as a species to exploring and discovering new ‘worlds’. It seems to be part of our Prime Directive.

How is “the human adventure” progressing, six months in? (I think I just made three veiled and cheesy ‘Star Trek’ references in the space of two sentences). Are you getting on each other’s nerves? Have you had to work through conflicts—(or romantic rivalries?)—and do you have some processes in place for ongoing conflict resolution and interpersonal catharsis? As a psychologist, this is what interests me most about your grand experiment. And I know that some scientists, by temperament and inclination, can tend to avoid the messiness and unpredictability of conflict, which will usually not just dissipate with time. (I know you have studied “Biosphere 2” on this matter!)

Enjoy your well-deserved vacation day and have fun! I look forward to hearing more about what you are all learning about the psychology of your mission.

Clear skies!

–Darrell

LikeLike

Dear Darell,

Thank you for this well-thought comment. You seem to know quite a lot about the mission.

You question is interesting. There is a limit to what I can disclose, but it still deserves a blog post. It will likely be the next one.

Thanks for the suggestion!

Cheers,

Cyprien

LikeLike